The Runaways

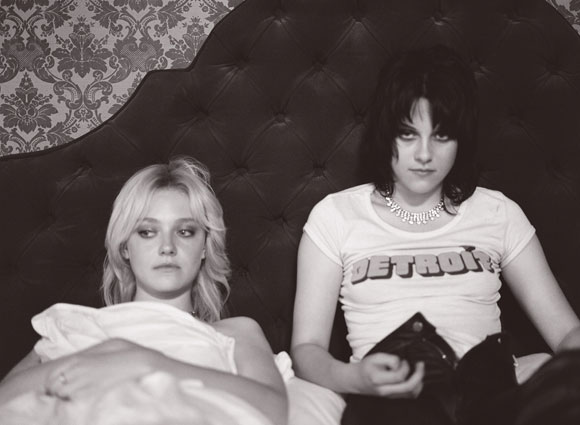

Dakota Fanning and Kristen Stewart star as Cherie Currie and Joan Jett in THE RUNAWAYS

Blood on the pavement—the opening shot—sets the tone for Floria Sigismondi’s biopic of the brief spark in the latter-70’s rock scene that was The Runaways. The boilerplate plot applies: humble origins, creepy producer giving them their first break, drugs, the big tour, the fall and the split. However, for her first feature, the Italian-born Ms. Sigismondi, whose previous credits include music videos for Marilyn Manson, David Bowie, Bjørk, The White Stripes and Muse, among others, has crafted a well-paced film with a woman’s perspective—a rarity in this subgenre.

The initiatory spatter signals entrance into womanhood for Cherie Currie (Dakota Fanning), a devotee of David Bowie’s androgynous Ziggy Stardust persona. Booed off a talent contest at school for emulating her hero, she defiantly gives the crowd the finger before she exits. Spending her nights at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco on the Sunset Strip, Currie meets wanna-be guitarist Joan Larkin (Kristen Stewart)—a.k.a. Jett, the leather-clad axe grinder inspired by Suzi Quatro—and the comically-sleazy Svengali, Kim Fowley (Michael Shannon, looking like a deranged cross between Michael C. Hall and Eddie Izzard). Says Fowley to the naif Currie, “If you want to be an artist, saw off your fucking ear and mail it to your boyfriend.” He puts them together with other musicians, including drummer Sandy West (Stella Maive) and lead guitarist Lita Ford (Scout Taylor-Compton). Absent from the story is founding bassist Micki (Michael) Steele, who later joined the Bangles, and Jackie Fox who was omitted for legal reasons—”Robin Robins” (Alia Shawkat) standing in.

The film—based on Ms. Currie’s memoir, Neon Angel—chronicles the band’s rapid ascent in 1976 from their initial formation to their signing with Mercury Records, by which time legends-to-be Van Halen and The Ramones were their opening acts. Writer/director Sigismondi focuses heavily on the two principals, band founder Jett and lead singer Currie, their friendship and emergent sexual exploration. We follow them from dive bar to hole-in-the-wall as they build their fan base, but the focus stays inward on the band.

While Cameron Crowe’s autobiographical love song to the period, Almost Famous, waxes poetic on the music and the muse from a journalist/fan’s perspective, The Runaways plays as fast and loose with the band’s biography as it does the camera. It lacks the richness of narrative possessed by Alex Cox’s Sid and Nancy, chiefly because the director intends here a crash course in Runaways history, rather than a narrower focus on a specific incident. Conversely, where Mr. Cox’s film employed mostly conventional scene compositions and static camera setups, cinematographer Benoît Debie (Irreversible, Enter the Void) foregoes staid arrangements for rock video superimpositions and cross-dissolves, as well as documentary-style hand-held work, all in a medium grain with a dingy palette that provokes my pathological aversion to the color brown—a consequence of 1970’s fashion. The sensibility toward teenage interests and idiosyncrasies matches Richard Linklater’s ode, Dazed and Confused, but as the band careens toward fame, Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine (vaguely biographing David Bowie) becomes the inspiration—an enraged Jett smashing a bottle and pounding the window of the studio control room. All of these films share a love for a period in which rock music made audacious statements for greater ends than feckless infatuations.

Ms. Sigismondi’s attention to small details adds to a well-textured look and feel. Running out of a rusty sardine can of a trailer after their first practice, Ms. Fanning trips over the curb as the camera opens out to a medium-wide shot. Other directors might have scrapped that take, but the scene evokes fond memories of childhood innocence. The shot is followed immediately by reckless abandon, drinking it up by the derelict, disintegrating “HOLLYWOOD” sign—restored two years later as the result of a public campaign led, incidentally, by shock rocker Alice Cooper. Near the film’s end, Joan is seen wearing a Cheap Trick t-shirt (one of many faithful replications of her wardrobe); that band was propelled to superstardom at Budokan Stadium the year following The Runaways’ performance at Tokyo Music Festival.

The director also treats two story elements differently than a man in her position might have. The film’s depiction of drug abuse avoids glamorizing the experience. It’s dizzy, unfocused, queasy, pale, bleak, depressing, pathetic and sad. When the camera shows off Currie in a racy outfit, it starkly opposes the vacant haze with which she answers her sister’s phonecall—ironically, concerning her father. Currie’s mixed relationship with her twin sister, Marie (Riley Keough), and her mother (Tatum O’Neal), becomes a recurring theme. Returning home to a medicated and recovering alcoholic, we’re not quite sure if, as she rifles through his pills, she’s trembling from withdrawal or the reality of a pathetic father. Like Claireece Jones (Gabourey Sidibe) in last year’s Precious, she must have to imagine a different life in order to barely function in this one.

While Ms. Fanning overacts at times, throwing her enunciation and body language too heavily into the character, her lack of finesse as an actress almost serves the awkward teen better, as in an early scene where she can’t seem to master the middle ground between placidly reading lyrics and belting them out. Ms. Stewart and Ms. Fanning actually sang the songs performed in the film. This, as in the case of the 2005 Johnny Cash biopic, Walk The Line, doesn’t necessarily benefit the story as much as it makes for a good publicity line in the same way big stars always love to talk about all the stunts they do themselves—rarely wise since it’s less important to see their faces than to see a stunt done correctly. But I’m not sure this was a stunt. The director may have wanted to maintain the energy and amateurish nature of the characters throughout. At that stage in their careers, neither Jett nor Currie could have been praised for technical prowess.

Ms. Stewart’s speed-shutter blinking and destitute moping, as in the Twilight series, is held completely in check here. Contrarily, she’s always moving—restless, fidgety—almost hyperactive, fiddling with her guitar or rocking back and forth in between sets. Leaning in to almost kiss her in a roller rink bathed in crimson light, aptly set to Iggy & The Stooges’ “I Wanna Be Your Dog”, Joan seductively blows smoke into Cherie’s mouth. A kicky scene, it’s contrast against the latter’s descent into drug addiction, paralleled with her father’s alcoholism and amplified by her mother’s constant absence. The relationship depicted between Jett and Currie consists chiefly of stares and glances, seldom traversing more meaningful ground. Then again, I’m not sure it gets much farther than lust for two teenagers still discovering their sexual identities.

Critic Nick Schager argues that Ms. Stewart and Ms. Fanning don’t have the chops to come off as anything but affectations of tough. Reviewing early interview footage of the real Joan Jett and Cherie Currie, I’ve concluded that’s precisely what they were—kids, emulating an edge. Thousands of cigarettes before Ms. Jett destroyed her voice, she came off every bit as green in a Tom Snyder interview (The Tomorrow Show, 1977) as Ms. Stewart in the film. That same year, a shy, inarticulate Ms. Currie interviewed with a pair of hosts during their Japan tour. They weren’t hardened criminals. These were children who became internationally famous before they could mentally process the enormity of it.

The Runaways is a competent, entertaining film that sticks mostly to the chronology with some character flourishes—Kim Fowley’s irreverent rants above all. Hampered by disputes over details, background characterizations suffer—most notably that of Lita Ford whose lead guitar-work embellished the band’s raw sound. Some scenes run a beat or two longer than necessary, the trimming of which would have tightened up the pace in the third act. Despite its flaws, it’s eminently watchable particularly for those, like myself, nostalgic for an era of brazen rock, uncluttered by today’s whiny, ineffectual Corgan and Yorke clones. If I haven’t commented here on the fact that Jett and Currie paved the road for many female rockers who followed, it’s because I fail to see the distinction. Actors are actors. Musicians are musicians. Road-tested, the Runaways have earned their place in rock history as equals among their male contemporaries.

Bonus: In the early stages of their touring, The Runaways opens for a band that mocks them during sound check. In response, Jett breaks into their dressing room and urinates on a guitar. Unmentioned in the film, the real Ms. Jett has unabashedly confirmed that the guitar, in fact, belonged to Alex Lifeson of Canadian progressive-rock band Rush.

The Runaways • Dolby® Digital surround sound in select theatres • Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1 • Running Time: 109 minutes • MPAA Rating: R for language, drug use and sexual content – all involving teens. • Distributed by Apparition